As a result of increasingly strict Western sanctions that blocked payment avenues to international creditors, Russia experienced its first sovereign default on foreign-currency debt in a century.

The nation worked around the sanctions imposed for many months after the Kremlin invaded Ukraine. But on Sunday evening, the grace period for nearly $100 million in overdue interest payments scheduled on May 27 ran out. Missing this date would be viewed as a default event.

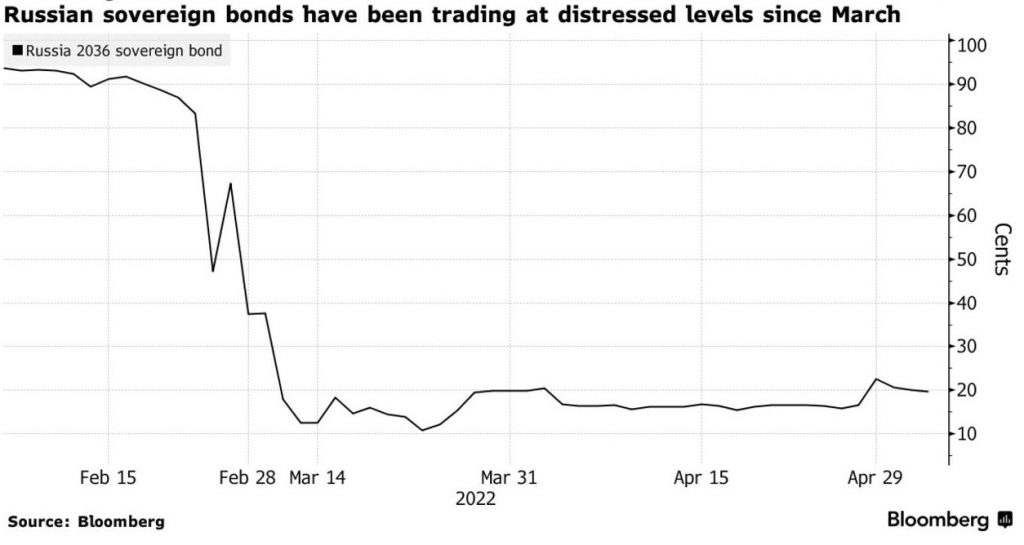

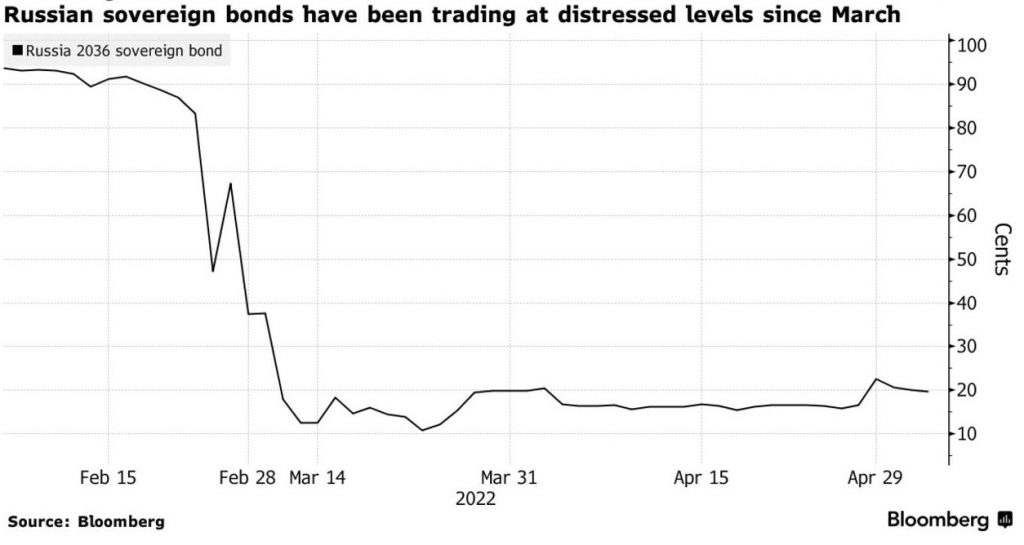

Since the beginning of March, the nation’s Eurobonds have traded at desperate prices, the central bank’s foreign reserves are frozen, and the largest banks are cut off from the rest of the world’s financial system.

The default, however, is also primarily symbolic for the time being, given the harm already done to the economy and markets. It means little to Russia, struggling with double-digit inflation and the worst economic turmoil in years.

Russia has resisted being designated default, claiming that it has the money to pay all of its debts and has been coerced into doing so. It started last week that it would move to pay its $40 billion in the outstanding national debt in rubles, trying to criticize the West for having fabricated a “force-majeure” situation.

Hassan Malik, a senior sovereign analyst at Loomis Sayles & Company LP, said,

“It’s a very, very rare thing, where a government that otherwise has the means is forced by an external government into default […] It’s going to be one of the big watershed defaults in history.”

Rating agencies would typically make a public pronouncement, but because of European sanctions, they have stopped rating Russian enterprises. Owners of 25% of the outstanding bonds must concur that an “Event of Default” has happened for holders of the notes whose grace period expired on Sunday to call one themselves.

The attention now moves to what investors should do after the last deadline has passed.

They are not required to take immediate action and may decide to watch the war’s development in the hopes that sanctions would ultimately be loosened. They may have the benefit of time because, according to the bond agreements, claims are only invalid three years after the payment date.

After the US Treasury let a loophole in the sanctions expire, it removed the exception that had permitted US bondholders to receive payments from the Russian sovereign, which led to the cash becoming stuck. A week later, the National Settlement Depository, Russia’s payment agency, also received sanctions from the European Union.

Vladimir Putin responded by introducing new laws that state that when the necessary sum in rubles has been paid to the regional payment agent, Russia’s obligations on foreign-currency bonds are met.

According to those regulations, the Finance Ministry paid its most recent interest payments on Thursday and Friday, totaling nearly $400 million. However, none of the underlying bonds have terms that allow for settlement in the local currency.

Investor usage of the new mechanism and whether current sanctions would even permit money to be repatriated are currently unknown.